- 概览

- Structure and Data Flow

- A Single Dispatcher

- Stores

- Views and Controller-Views

- Actions

- What About that Dispatcher?

- Structure and Data Flow

概览

Flux is the application architecture that Facebook uses for building client-side web applications. It complements React’s composable view components by utilizing a unidirectional data flow. It’s more of a pattern rather than a formal framework, and you can start using Flux immediately without a lot of new code.

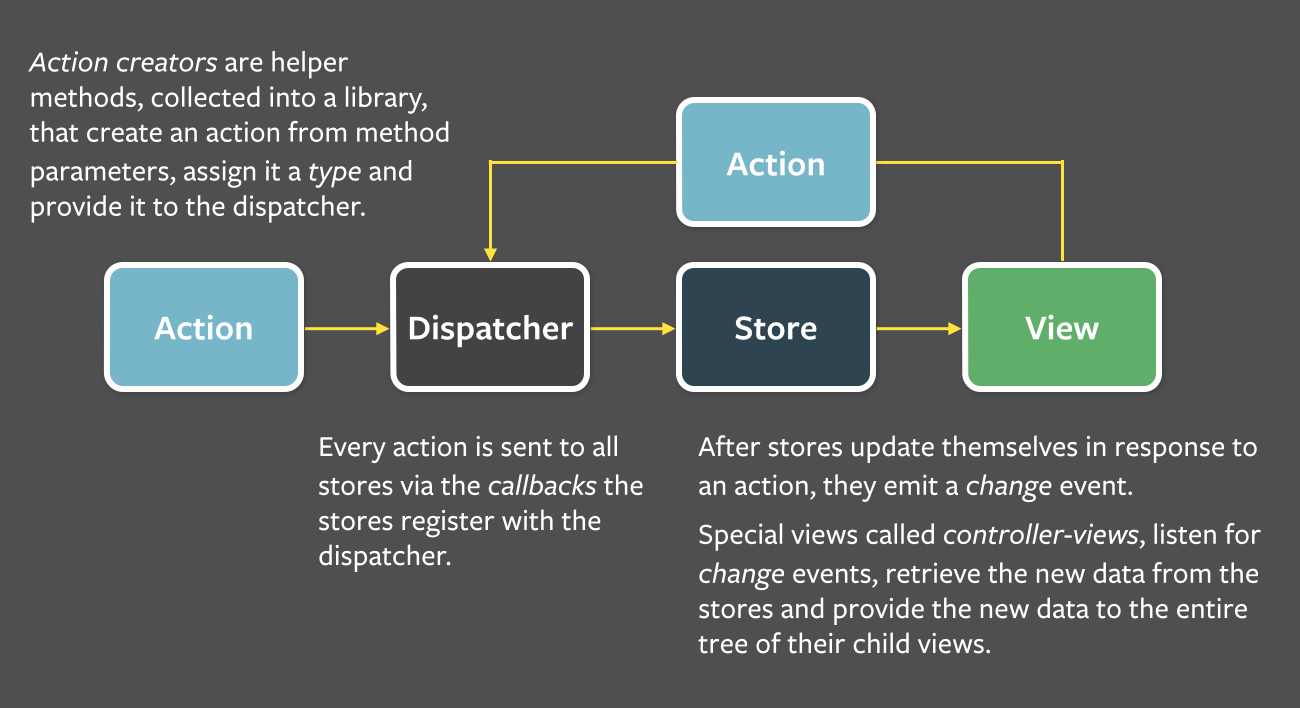

Flux applications have three major parts: the dispatcher, the stores, and the views (React components). These should not be confused with Model-View-Controller. Controllers do exist in a Flux application, but they are controller-views — views often found at the top of the hierarchy that retrieve data from the stores and pass this data down to their children. Additionally, action creators — dispatcher helper methods — are used to support a semantic API that describes all changes that are possible in the application. It can be useful to think of them as a fourth part of the Flux update cycle.

Flux eschews MVC in favor of a unidirectional data flow. When a user interacts with a React view, the view propagates an action through a central dispatcher, to the various stores that hold the application’s data and business logic, which updates all of the views that are affected. This works especially well with React’s declarative programming style, which allows the store to send updates without specifying how to transition views between states.

We originally set out to deal correctly with derived data: for example, we wanted to show an unread count for message threads while another view showed a list of threads, with the unread ones highlighted. This was difficult to handle with MVC — marking a single thread as read would update the thread model, and then also need to update the unread count model. These dependencies and cascading updates often occur in a large MVC application, leading to a tangled weave of data flow and unpredictable results.

Control is inverted with stores: the stores accept updates and reconcile them as appropriate, rather than depending on something external to update its data in a consistent way. Nothing outside the store has any insight into how it manages the data for its domain, helping to keep a clear separation of concerns. Stores have no direct setter methods like setAsRead(), but instead have only a single way of getting new data into their self-contained world — the callback they register with the dispatcher.

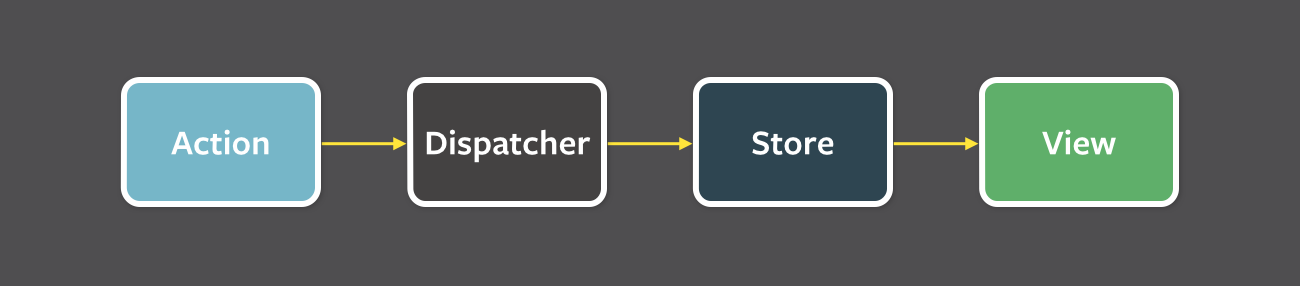

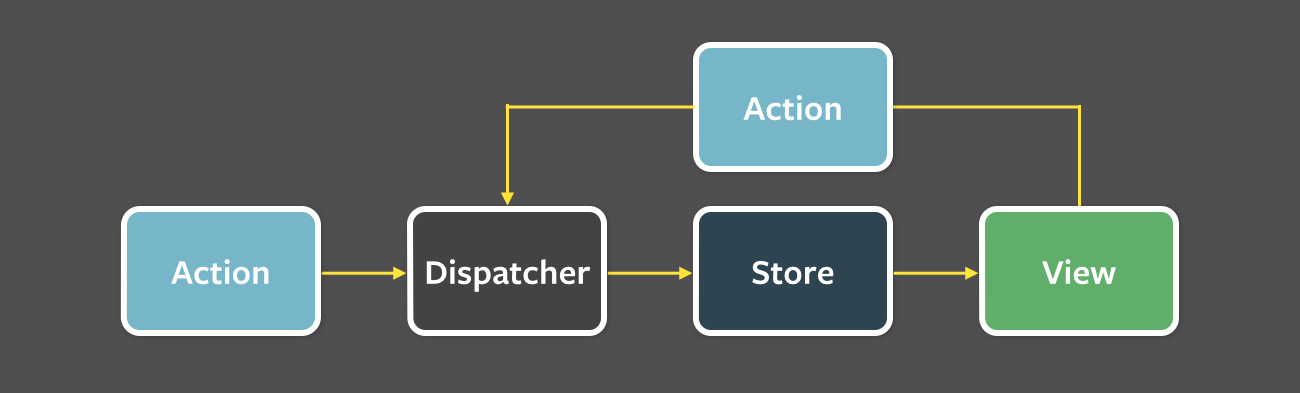

Structure and Data Flow

A unidirectional data flow is central to the Flux pattern, and the above diagram should be the primary mental model for the Flux programmer. The dispatcher, stores and views are independent nodes with distinct inputs and outputs. The actions are simple objects containing the new data and an identifying type property.

This structure allows us to reason easily about our application in a way that is reminiscent of functional reactive programming, or more specifically data-flow programming or flow-based programming, where data flows through the application in a single direction — there are no two-way bindings. Application state is maintained only in the stores, allowing the different parts of the application to remain highly decoupled. Where dependencies do occur between stores, they are kept in a strict hierarchy, with synchronous updates managed by the dispatcher.

We found that two-way data bindings led to cascading updates, where changing one object led to another object changing, which could also trigger more updates. As applications grew, these cascading updates made it very difficult to predict what would change as the result of one user interaction. When updates can only change data within a single round, the system as a whole becomes more predictable.

Let’s look at the various parts of Flux up close. A good place to start is the dispatcher.

A Single Dispatcher

The dispatcher is the central hub that manages all data flow in a Flux application. It is essentially a registry of callbacks into the stores and has no real intelligence of its own — it is a simple mechanism for distributing the actions to the stores. Each store registers itself and provides a callback. When an action creator provides the dispatcher with a new action, all stores in the application receive the action via the callbacks in the registry.

As an application grows, the dispatcher becomes more vital, as it can be used to manage dependencies between the stores by invoking the registered callbacks in a specific order. Stores can declaratively wait for other stores to finish updating, and then update themselves accordingly.

The same dispatcher that Facebook uses in production is available through npm, Bower, or GitHub.

Stores

Stores contain the application state and logic. Their role is somewhat similar to a model in a traditional MVC, but they manage the state of many objects — they do not represent a single record of data like ORM models do. Nor are they the same as Backbone’s collections. More than simply managing a collection of ORM-style objects, stores manage the application state for a particular domain within the application.

For example, Facebook’s Lookback Video Editor utilized a TimeStore that kept track of the playback time position and the playback state. On the other hand, the same application’s ImageStore kept track of a collection of images. The TodoStore in our TodoMVC example is similar in that it manages a collection of to-do items. A store exhibits characteristics of both a collection of models and a singleton model of a logical domain.

As mentioned above, a store registers itself with the dispatcher and provides it with a callback. This callback receives the action as a parameter. Within the store’s registered callback, a switch statement based on the action’s type is used to interpret the action and to provide the proper hooks into the store’s internal methods. This allows an action to result in an update to the state of the store, via the dispatcher. After the stores are updated, they broadcast an event declaring that their state has changed, so the views may query the new state and update themselves.

Views and Controller-Views

React provides the kind of composable and freely re-renderable views we need for the view layer. Close to the top of the nested view hierarchy, a special kind of view listens for events that are broadcast by the stores that it depends on. We call this a controller-view, as it provides the glue code to get the data from the stores and to pass this data down the chain of its descendants. We might have one of these controller-views governing any significant section of the page.

When it receives the event from the store, it first requests the new data it needs via the stores’ public getter methods. It then calls its own setState() or forceUpdate() methods, causing its render() method and the render() method of all its descendants to run.

We often pass the entire state of the store down the chain of views in a single object, allowing different descendants to use what they need. In addition to keeping the controller-like behavior at the top of the hierarchy, and thus keeping our descendant views as functionally pure as possible, passing down the entire state of the store in a single object also has the effect of reducing the number of props we need to manage.

Occasionally we may need to add additional controller-views deeper in the hierarchy to keep components simple. This might help us to better encapsulate a section of the hierarchy related to a specific data domain. Be aware, however, that controller-views deeper in the hierarchy can violate the singular flow of data by introducing a new, potentially conflicting entry point for the data flow. In making the decision of whether to add a deep controller-view, balance the gain of simpler components against the complexity of multiple data updates flowing into the hierarchy at different points. These multiple data updates can lead to odd effects, with React’s render method getting invoked repeatedly by updates from different controller-views, potentially increasing the difficulty of debugging.

Actions

The dispatcher exposes a method that allows us to trigger a dispatch to the stores, and to include a payload of data, which we call an action. The action’s creation may be wrapped into a semantic helper method which sends the action to the dispatcher. For example, we may want to change the text of a to-do item in a to-do list application. We would create an action with a function signature like updateText(todoId, newText) in our TodoActions module. This method may be invoked from within our views’ event handlers, so we can call it in response to a user interaction. This action creator method also adds a type to the action, so that when the action is interpreted in the store, it can respond appropriately. In our example, this type might be named something like TODO_UPDATE_TEXT.

Actions may also come from other places, such as the server. This happens, for example, during data initialization. It may also happen when the server returns an error code or when the server has updates to provide to the application.

What About that Dispatcher?

As mentioned earlier, the dispatcher is also able to manage dependencies between stores. This functionality is available through the waitFor() method within the Dispatcher class. We did not need to use this method within the extremely simple TodoMVC application, but it becomes vital in a larger, more complex application.

Within the TodoStore’s registered callback we could explicitly wait for any dependencies to first update before moving forward:

case 'TODO_CREATE':Dispatcher.waitFor([PrependedTextStore.dispatchToken,YetAnotherStore.dispatchToken]);TodoStore.create(PrependedTextStore.getText() + ' ' + action.text);break;

waitFor() accepts a single argument which is an array of dispatcher registry indexes, often called dispatch tokens. Thus the store that is invoking waitFor() can depend on the state of another store to inform how it should update its own state.

A dispatch token is returned by register() when registering callbacks for the Dispatcher:

PrependedTextStore.dispatchToken = Dispatcher.register(function (payload) {// ...});

For more on waitFor(), actions, action creators and the dispatcher, please see Flux: Actions and the Dispatcher.